RAW: Craft, Commodity, and Capitalism

RAW: Craft, Commodity, and Capitalism

Curated by Holly Jerger,

Craft Contemporary, Los Angeles, CA

R AW : C R A F T, C O M M O D I T Y, A N D C A P I TA L I S M has been a labor of love for curator Holly Jerger, who first conceived of this exhibition in 2015. The exhibition explores the artists’ conscious use of material to create meaning and calls our attention to the hidden histories of everyday materials we often take for granted.

R AW: C R A F T, CO M M O D I T Y, A N D C A P I TA L I S M features nine contemporary artists who work with commodities including sugar, salt, copper, porcelain, and water to explore the historical and contemporary effects of global capitalism. The artists’ deliberate use of these materials acknowledges the complex and enduring legacy of the capitalistic structures that produced these raw materials, such as slavery, colonialism, and industrialization, and their ongoing human and environmental impact.

Juana Valdes examines the ongoing ramifications of globalization and migration in postcolonial history by highlighting the history of objects and the materials from which they are made. She states, “I sustain a multi-disciplinary practice that explores matters of race, transnationalism, gender, labor, and class. My work functions as an archive that analyzes and decodes the intersectionality of objects by investigating their history of origin.”

Valdes often utilizes porcelain in her work for its history as one of the earliest globalized commodities and objects of transcultural exchange. Starting in the 10th century, Chinese porcelain centers began exporting their products, and porcelain played a central role in cross-cultural exchange between Asia, Africa, and Europe. Chinese porcelain was often referred to as “white gold” and was renown for its smooth texture, bright white color, and translucency. Chinese porcelain wares were disseminated globally and influenced virtually all ceramic traditions they touched. Simultaneously, Chinese porcelain production was influenced by the tastes of the varied markets under its reach. China maintained its hold on the global exchange of the material until European factories started producing their own versions of porcelain wares in the 18th century.

Through her porcelain works, Valdes questions how systems of economic and aesthetic value are embedded within domestic objects. For her work, SED(-to thirst), 2017, Valdes casts a set of plastic water bottles in porcelain. The water brand, Sei, is a particularly expensive “artisanal” water. The disposable plastic bottles are now rendered in clay, equating them to the status of traditional porcelain vessels. Valdes seems to ask if that prestige is due to the water bottles’ actual value, or the perceived status they impart on those who can afford to buy them.

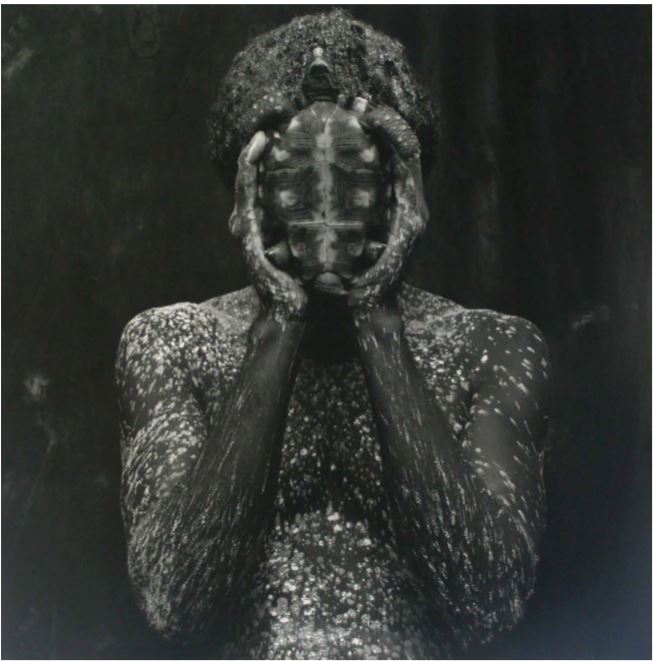

In RedBone Colored China Rags, 2012, Valdes utilizes bone china, a particular form of porcelain developed in Britain in 1794, in which bone ash was added to the clay body to better imitate the high level of whiteness and translucency found in Chinese porcelain. Valdes upends those key properties of the porcelain by adding pigment to create a range of opaque skin tones in the form of cleaning rags. Valdes subverts the traditional aesthetic expectations for bone china objects in order to recognize the domestic workers, typically women of color, who have been responsible for caring for these ceramic objects over the centuries. Valdes’s forms directly reference these women’s bodies and labor, asserting their contributions to the historical preservation of these objects. She also seeks to dismantle racialized Eurocentric standards of beauty in which whiteness is prioritized and its connection to the lasting impact of colonialization.

VIDEO

VIDEO

VIRTUAL TOUR

Explore other exhibitions

%20Large.jpeg)